Want Your Children to Survive The Future? Send Them to Art School

Can you imagine a world in which most jobs are obsolete?

If not, you are most likely in for a rude awakening in the coming decades of radical shifts in employment. This is particularly true for new parents propelling the next generation of workers into an adulthood that many economists and futurists predict to be the first ever “post-work” society.

Though the idea of a jobless world may seem radical, the prediction is based on the natural trajectory of ‘creative destruction’ — that classic economic principle by which established industries are decimated when made irrelevant by new technologies.

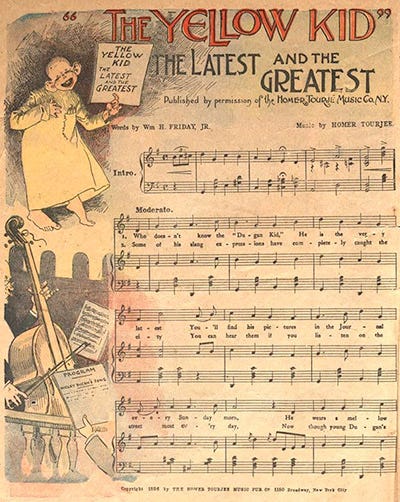

When was the last time you picked up the hot new single from your local sheet music store? Many moons ago sheet music was the music industry, with the only available means of hearing pop songs being to have a musician read and perform them. This quickly eroded with the advent of the phonograph, leading to a record industry that dominated the last century and is now itself eroding due to the explosive growth of independent online publishing.

It’s hard to justify using a massive workforce of recording engineers, media manufacturers, distributors, and talent scouts to accomplish a task that a musician can now do by herself in an afternoon with just a laptop. The same goes for the millions of skilled labor and manufacturing jobs that will soon be crumpled by 3D printing technology, the thousands of retailers whose staff and storefronts can readily be supplanted by automated delivery systems, or the dwindling hospitality and transportation industries currently being pecked away by app-based sharing services like Airbnb and Uber.

Never heard of 3D printing, ridesharing, or “post-work” theory? That’s okay; you can just Google them. In fact, thanks to Google we may now add the very concept of knowledge itself to our growing list of no-longer-scarce resources. When anyone can access the world’s greatest library from their cellphone, even the long-revered skill of knowing things loses its marketability.

The Art School Solution

Photo by Jeff White, courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment

If preparing your kids for a world in which hard-working, knowledgeable people are unemployable frightens you then I have some good news. There is a solution, and it doesn’t involve tired, useless attempts at suppressing technology. Like most good solutions it requires a trait that is distinctly human.

I’m speaking about Creativity.

Send your kids to art school. Heavily invest time and resources into their creative literacy. Do these things and they will stand a chance at finding work and or fulfillment in a future where other human abilities become irrelevant.

Any adult reading this at the time of publication came of age in an era when parents urged children to learn a subject that would funnel straight into a specific career field. Even those parents who encouraged their children’s creative dreams did so with an addendum that we should also consider getting a degree in a practical field that “you can always fall back on if sculpture/philosophy/theater/poetry doesn’t work out”. No doubt this protective instinct was a smart one considering the reality of our youth. An arts education might promise a life of self-discovery but there has always been reasonably assured financial stability in the high-demand arenas of science, education, skilled trades, governments, etc. Surely that dynamic won’t last much longer as more and more physical and mental human tasks are commandeered by machines and software.

Photo courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment

Photo courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & EntertainmentI don’t say this to dismiss the importance of any field of study. A world without scientists or doctors or teachers would be just as broken as a world with no artists. Without programmers and engineers the very technologies that make life efficient would quickly disappear. But with the abundance of information and tools freely accessible online to a generation of youngsters equipped with computers from toddlerhood, it’s safe to assume that those who want to maintain current technology have few obstacles in learning how to do so — No degree required. The same goes for any pragmatic skill.

The arts, however, are a polar opposite to pragmatism. Cameras have long exceeded our ability to realistically and efficiently render images, but still our love of painting remains to this day. By now we know that the value of a great painting isn’t in its accuracy at rendering a view but in the artist’s unique capacity to convey a viewpoint. Even those uninterested in “fine” art are driven to make purely aesthetic decisions on practical matters such as clothing, shelter, and transportation. Our willingness to pay extra for beautiful clothes, inviting homes, and sleek cars is motivated not by functionality but by emotionality.

Photo courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment

It’s inherently human to want the objects in our lives to communicate feelings and ideas to us and about us. The constant searching for and assignment of meaning dwells in everyone, but the artist is the person who exercises this muscle regularly enough to control it. The person with creative literacy — a basic understanding of the mental, emotional, and sociological tools used for creative thought and communication — is able to find purpose and apply meaning to her world rather than having meaning handed down and purpose assigned to her. The painting student completes his senior thesis exhibit with a head full of many more lessons than just how to paint. He’s now equipped with an ability to see problems, connections, and solutions where others see only a blank surface. I assure you this ability is not limited to the canvas.

Photo Courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment

Photo Courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & EntertainmentI’m not saying anything new here. These qualities of a liberal arts education have been expounded by its proprietors for ages, but with major industries quickly running out of a need for worker bees it’s becoming clearer by the day that our professors were right.

In fact it’s somewhat amazing that this idea was ever in question. Humanity’s highest-paid workers have always been those who as a result of their innovations created opportunity for others to work.

There’s a reason Steve Jobs became a billionaire, and it’s not because he could program computers.

Of course history is also filled with countless stories of equally creative figures lost in the systemic grind of working for the Steve Jobs’s of the world. We’ve all known brilliant people, seemingly not made for our time, whose potential was crushed by dead end jobs after their work was rejected by the film/music/publishing/anything industries. The excuse of being ahead of one’s time can no longer apply though. We live in an age where a person speaking into a webcam can collectively raise hundreds of thousands of dollars just by telling people about a good idea. The gatekeepers are gone and they are not coming back. Our only remaining obstacle can be lack of good ideas.

It’s time for a revolution in education that reflects our new reality and gives students the necessary tools to survive it. Technological advancements will always outpace the offerings of the traditional classroom, making it entirely purposeless to force memorization of knowledge that may become irrelevant before children even graduate. Instead we should hone the skill that best ensures adaptability and resourcefulness during times of constant change.

It’s time for the creative classroom.

But what about STEM?

Does this revolution require us to toss out math or science or history? Does my ideal future classroom wedge would-be physicists into an endless curriculum of figure drawing classes?

Absolutely not!

Let children pursue their own interests and they will find their way to all areas of study as part of the exploratory process. Let the child who is in love with fire trucks continue to obsess over fire trucks. With proper guidance he will soon find himself learning civics, engineering, history, physics, chemistry, sociology, economics, and everything in between — all of his questions fueled by a simple aesthetic attachment to the pretty red fire truck.

No healthy child is born without an innate sense of wonder about their world. However, this childhood compulsion to explore is a bud quickly snipped by adults conditioned to fear the unknown. The tradition of discouraging unusual questions and behavior in children is so pervasive that we have come to view those who survive with their creativity intact as having a “gift”. What is more absurd is our amazement at the correlation of great artists and mental illness, as if the battle for self-expression which artists so tenaciously endure has no causal link to their psychic well-being.

Photo Courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment

Photo Courtesy of Lowe Mill ARTS & EntertainmentThe change that will secure your children’s safe passage through the future comes when we strip creativity of its mysterious, unearthly status. Artists are not magical geniuses. We are simply people who were either privileged enough or stubborn enough to hold onto something that every living person is “gifted” at birth. Assume that your children have limitless creative potential and begin to nurture it. Assume that your children’s ingenuity is the one true safety net available in times of rapid change. Send your kids to art school and they will have exactly what they need to become anything they might need to be.

I speak from experience.

Photo by Eric Schultz, Huntsville Times

Photo by Eric Schultz, Huntsville TimesDustin Timbrook is an artist in Huntsvill

If in doubt, install an art slide. From the Czech mountains to Stratford, slides are now defined as both fun and cultural. Art is turning into play, and play now seen as a noble cultural goal for adults as well as children.

If in doubt, install an art slide. From the Czech mountains to Stratford, slides are now defined as both fun and cultural. Art is turning into play, and play now seen as a noble cultural goal for adults as well as children.