In a recent newsletter from

Brain Pickings, Maria Popova looked at the notion of creativity.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly interestingness digest. It

comes out on Sundays and offers excellent articles from the week. The original article can be read at

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/09/06/what-is-creativity/

Bradbury, Eames, Angelou, Gladwell, Einstein,

Byrne, Duchamp, Close, Sendak, and more.

“Creativity” is one of those grab-bag

terms, like “happiness” and “love,” that can mean so many things it runs

the risk of meaning nothing at all. And yet some of history’s greatest

minds have attempted to capture, explain, describe, itemize, and dissect

the nature of creativity. After similar omnibi of cultural icons’ most

beautiful and articulate definitions

of

art,

of

science, and

of

love, here comes one of creativity.

For

Ray Bradbury, creativity was

the

art of muting the rational mind:

The intellect is a great danger to creativity … because

you begin to rationalize and make up reasons for things, instead of

staying with your own basic truth — who you are, what you are, what you

want to be. I’ve had a sign over my typewriter for over 25 years now,

which reads “Don’t think!” You must never think at the typewriter — you

must feel. Your intellect is always buried in that feeling anyway. … The

worst thing you do when you think is lie — you can make up reasons that

are not true for the things that you did, and what you’re trying to do

as a creative person is surprise yourself — find out who you really are,

and try not to lie, try to tell the truth all the time. And the only

way to do this is by being very active and very emotional, and get it

out of yourself — making things that you hate and things that you love,

you write about these then, intensely.

Long before he was became

the

artist we know and love, a young

Maurice Sendak

full of self-doubt wrote in a letter to his editor, the remarkable

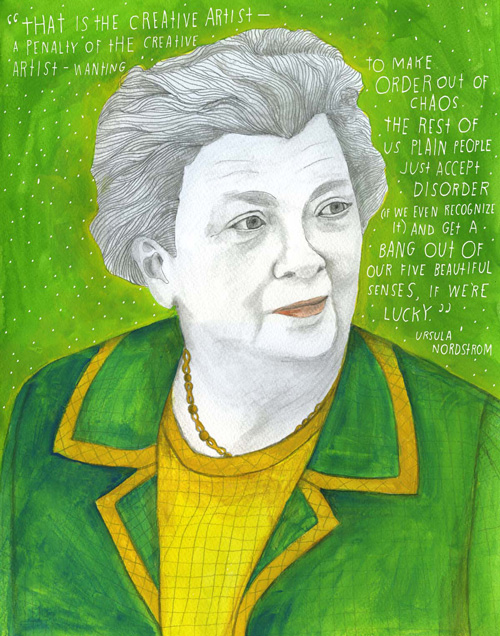

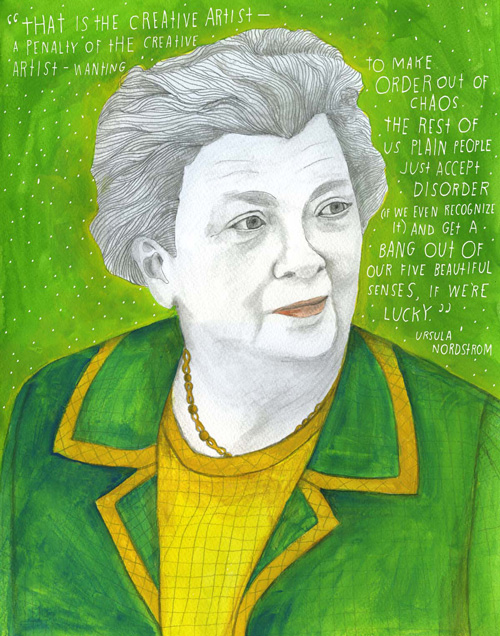

Ursula Nordstrom:

Knowledge is the driving force that puts creative passion

to work.

In

writing back, Nordstrom responded with her signature blend of

wisdom and assurance:

That is the creative artist — a penalty of the creative

artist — wanting to make order out of chaos.

Portrait by Lisa Congdon for our Reconstructionists project.

Click image for details.

Bill Moyers is

credited with having offered a sort of mirror-image

definition that does away with order and seeks, instead, magical chaos:

Creativity is piercing the mundane to find the marvelous.

For

Albert Einstein, its defining characteristic was

what he called

“combinatory

play”. In a letter to a French mathematician, included in

Einstein’s

Ideas and Opinions (

public library), he writes:

The words or the language, as they are written or spoken,

do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical

entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs

and more or less clear images which can be “voluntarily” reproduced and

combined.

There is, of course, a certain connection between those elements and

relevant logical concepts. It is also clear that the desire to arrive

finally at logically connected concepts is the emotional basis of this

rather vague play with the above-mentioned elements. But taken from a

psychological viewpoint, this combinatory play seems to be the essential

feature in productive thought — before there is any connection with

logical construction in words or other kinds of signs which can be

communicated to others.

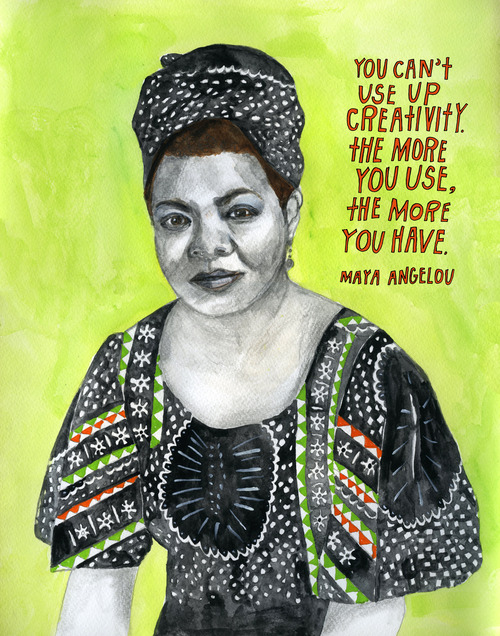

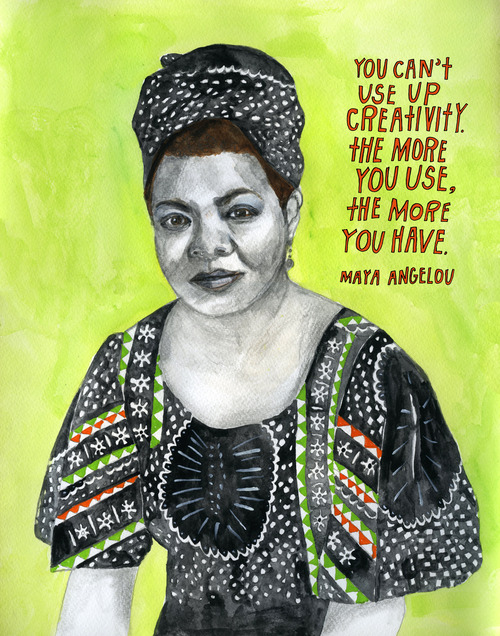

Portrait by Lisa Congdon for our Reconstructionists project.

Click image for details.

For

Maya Angelou, a

modern-day

sage of the finest kind, the mystery and miracle of creativity is

in its self-regenerating nature. In the excellent collection

Conversations with Maya Angelou

(

public library), which also gave us her

poignant

exchange with Bill Moyers, Angelou says:

Creativity or talent, like electricity, is something I

don’t understand but something I’m able to harness and use. While

electricity remains a mystery, I know I can plug into it and light up a

cathedral or a synagogue or an operating room and use it to help save a

life. Or I can use it to electrocute someone. Like electricity,

creativity makes no judgment. I can use it productive or destructively.

The important thing is to use it. You can’t use up creativity. The more

you use it, the more you have.

Tom Bissell, writing in

Magic

Hours: Essays on Creators and Creation, also

celebrates this magical quality of creativity:

To create anything … is to believe, if only momentarily,

you are capable of magic. … That magic … is sometimes perilous,

sometimes infectious, sometimes fragile, sometimes failed, sometimes

infuriating, sometimes triumphant, and sometimes tragic.

But there might be something more precise and less mystical about the

creative process. In

Uncommon Genius: How Great Ideas Are Born

(

public library), the fantastic collection

of interviews with MacArthur “genius” grantees by

Denise

Shekerjian, she recapitulates her findings:

The trick to creativity, if there is a single useful

thing to say about it, is to identify your own peculiar talent and then

to settle down to work with it for a good long time.

Shekerjian interviews the late

Stephen Jay Gould,

arguably

the

best science writer of all time, who describes his own approach to

creativity as

the

art of making connections, which Shekerjian synthesizes:

Gould’s special talent, that rare gift for seeing the

connections between seemingly unrelated things, zinged to the heart of

the matter. Without meaning to, he had zeroed in on the most popular of

the manifold definitions of creativity: the idea of connecting two

unrelated things in an efficient way. The surprise we experience at such

a linkage brings us up short and causes us to think, Now that’s

creative.

This notion, of course, is not new. In his timelessly insightful 1939

treatise

A Technique for Producing Ideas

(

public library), outlining the

five

stages of ideation,

James Webb Young asserts:

An idea is nothing more nor less than a new combination

of old elements [and] the capacity to bring old elements into new

combinations depends largely on the ability to see relationships. The

habit of mind which leads to a search for relationships between facts

becomes of the highest importance in the production of ideas.

Three years later, in 1942,

Rosamund Harding added

another dimension of stressing the importance of cross-disciplinary

combinations in wonderful out-of-print tome

An

Anatomy of Inspiration:

Originality depends on new and striking combinations of

ideas. It is obvious therefore that the more a man knows the greater

scope he has for arriving at striking combinations. And not only the

more he knows about his own subject but the more he knows beyond it

of other subjects. It is a fact that has not yet been sufficiently

stressed that those persons who have risen to eminence in arts, letters

or sciences have frequently possessed considerable knowledge of subjects

outside their own sphere of activity.

Seven decades later,

Phil Beadle echoes this concept

in his wonderful blueprint

field

guide to creativity,

Dancing About Architecture: A Little Book

of Creativity (

public library):

It is the ability to spot the potential in the product of

connecting things that don’t ordinarily go together that marks out the

person who is truly creative.

Steve Jobs famously

articulated this notion and took it a step further, emphasizing the

importance of building a rich personal library of experiences and ideas

to connect:

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask

creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty

because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed

obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect

experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they

were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have

thought more about their experiences than other people. Unfortunately,

that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had

very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect,

and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective

on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience,

the better design we will have.

Musician

Amanda Palmer puts this even more

poetically in her

meditation

on dot-connecting and creativity:

We can only connect the dots that we collect, which makes

everything you write about you. … Your connections are the thread that

you weave into the cloth that becomes the story that only you can tell.

Beloved graphic designer

Paula Scher has a different

metaphor for the same concept. In Debbie Millman’s

How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer

(

UK;

public library), she

likens

creativity to a slot machine:

There’s a certain amount of intuitive thinking that goes

into everything. It’s so hard to describe how things happen intuitively.

I can describe it as a computer and a slot machine. I have a pile of

stuff in my brain, a pile of stuff from all the books I’ve read and all

the movies I’ve seen. Every piece of artwork I’ve ever looked at. Every

conversation that’s inspired me, every piece of street art I’ve seen

along the way. Anything I’ve purchased, rejected, loved, hated. It’s all

in there. It’s all on one side of the brain.

And on the other side of the brain is a specific brief that comes

from my understanding of the project and says, okay, this solution is

made up of A, B, C, and D. And if you pull the handle on the slot

machine, they sort of run around in a circle, and what you hope is that

those three cherries line up, and the cash comes out.

But

Arthur Koestler, in his seminal 1964 anatomy of

creativity,

The Act Of Creation (

public library), argues that besides

connection, the creative act necessitates contrast, or what he termed

“bisociation”:

The pattern underlying [the creative act] is the

perceiving of a situation or idea in two self-consistent but habitually

incompatible frames of references. The event, in which the two

intersect, is made to vibrate simultaneously on two different

wavelengths, as it were. While this unusual situation lasts, [the event]

is not merely linked to one associative context, but bisociated with

two.

I have coined the term ‘bisociation’ in order to make a distinction

between the routine skills of thinking on a single ‘plane,’ as it were,

and the creative act, which … always operates on more than one plane.

The former can be called single-minded, the latter double-minded,

transitory state of unstable equilibrium where the balance of both

emotion and thought is disturbed.

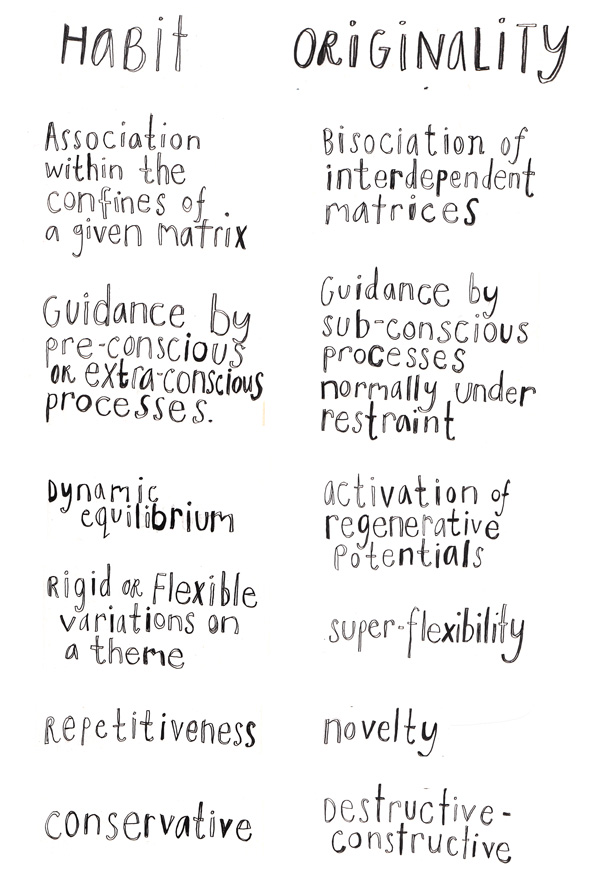

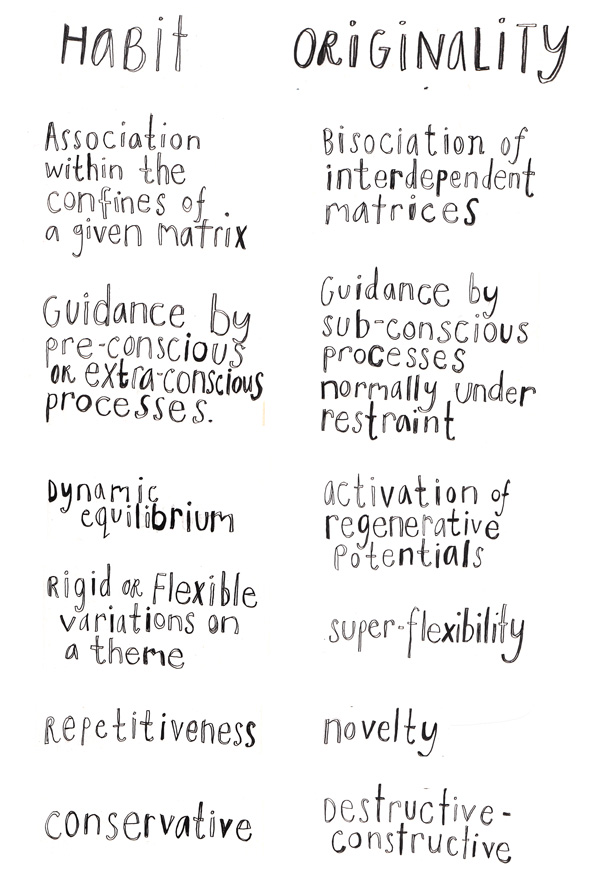

He differentiated between cognitive habit, or merely associative

thought, and originality, or bisociative ideation, thusly:

Twenty years later, creative icon and original Mad Man

George

Lois echoed Koestler in his influential tome

The Art of Advertising: George Lois on Mass

Communication (

public library):

Creativity can solve almost any problem. The creative

act, the defeat of habit by originality, overcomes everything.

For

Gretchen Rubin, however, habit isn’t the enemy

of creativity but its engine. In

Manage

Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your

Creative Mind, she writes:

Anthony Trollope, the nineteenth-century writer who

managed to be a prolific novelist while also revolutionizing the British

postal system, observed, “A small daily task, if it be really daily,

will beat the labours of a spasmodic Hercules.” Over the long run, the

unglamorous habit of frequency fosters both productivity and creativity.

[…]

You’re much more likely to spot surprising relationships and to see

fresh connections among ideas, if your mind is constantly humming with

issues related to your work. … By contrast, working sporadically makes

it hard to keep your focus. It’s easy to become blocked, confused, or

distracted, or to forget what you were aiming to accomplish.

[…]

Creativity arises from a constant churn of ideas, and one of the

easiest ways to encourage that fertile froth is to keep your mind

engaged with your project. When you work regularly, inspiration strikes

regularly.

In 1926, English social psychologist and London School of Economics

co-founder

Graham Wallas penned

The Art of Thought,

laying out his theory for how creativity works. Its gist, preserved in

the altogether indispensable

The Creativity Question (

public library), identifies the four

stages of the creative process —

preparation,

incubation, illumination, and verification — and their essential

interplay:

In the daily stream of thought these four different

stages constantly overlap each other as we explore different problems.

An economist reading a Blue Book, a physiologist watching an experiment,

or a business man going through his morning’s letters, may at the same

time be “incubating” on a problem which he proposed to himself a few

days ago, be accumulating knowledge in “preparation” for a second

problem, and be “verifying” his conclusions on a third problem. Even in

exploring the same problem, the mind may be unconsciously incubating on

one aspect of it, while it is consciously employed in preparing for or

verifying another aspect. And it must always be remembered that much

very important thinking, done for instance by a poet exploring his own

memories, or by a man trying to see clearly his emotional relation to

his country or his party, resembles musical composition in that the

stages leading to success are not very easily fitted into a “problem and

solution” scheme. Yet, even when success in thought means the creation

of something felt to be beautiful and true rather than the solution of a

prescribed problem, the four stages of Preparation, Incubation,

Illumination, and the Verification of the final result can generally be

distinguished from each other.

But

Malcolm Gladwell, in

reflecting on the legacy of legendary economist

Albert O. Hirscham in his review of

Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O.

Hirschman, doesn’t think the creative process is so deliberate:

Creativity always comes as a surprise to us; therefore we

can never count on it and we dare not believe in it until it has

happened. In other words, we would not consciously engage upon tasks

whose success clearly requires that creativity be forthcoming. Hence,

the only way in which we can bring our creative resources fully into

play is by misjudging the nature of the task, by presenting it to

ourselves as more routine, simple, undemanding of genuine creativity

than it will turn out to be.

But

David Byrne is skeptical of this romantic notion

that creativity is a purely subconscious muse that dances to its own

mystical drum. In

How Music Works (

public library), one of

the

best music books of 2012, he writes:

I had an extremely slow-dawning insight about creation.

That insight is that context largely determines what is written,

painted, sculpted, sung, or performed. That doesn’t sound like much of

an insight, but it’s actually the opposite of conventional wisdom, which

maintains that creation emerges out of some interior emotion, from an

upwelling of passion or feeling, and that the creative urge will brook

no accommodation, that it simply must find an outlet to be heard, read,

or seen. The accepted narrative suggests that a classical composer gets a

strange look in his or her eye and begins furiously scribbling a fully

realized composition that couldn’t exist in any other form. Or that the

rock-and-roll singer is driven by desires and demons, and out bursts

this amazing, perfectly shaped song that had to be three minutes and

twelve seconds — nothing more, nothing less. This is the romantic notion

of how creative work comes to be, but I think the path of creation is

almost 180º from this model. I believe that we unconsciously and

instinctively make work to fit preexisting formats.

Of course, passion can still be present. Just because the form that

one’s work will take is predetermined and opportunistic (meaning one

makes something because the opportunity is there), it doesn’t mean that

creation must be cold, mechanical, and heartless. Dark and emotional

materials usually find a way in, and the tailoring process — form being

tailored to fit a given context — is largely unconscious, instinctive.

We usually don’t even notice it. Opportunity and availability are often

the mother of invention.

For

John Cleese, creativity is neither a conscious

plan of attack nor an unconscious mystery, but a mode of being. In his

superb

1991

talk on the five factors of creativity, he asserts in his

characteristic manner of laconic wisdom:

Creativity is not a talent. It is a way of operating.

In

Inside the Painter’s Studio

(

public library), celebrated artist

Chuck

Close is even more exacting in his take on this “way of

operating,”

equating

creativity with work ethic:

Inspiration is for amateurs — the rest of us just show up

and get to work.

In his short 1957 paper

The

Creative Act, French surrealist icon

Marcel Duchamp

considers the work of creativity a participatory project involving both

creator and spectator:

The creative act is not performed by the artist alone;

the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by

deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his

contribution to the creative act. This becomes even more obvious when

posterity gives a final verdict and sometimes rehabilitates forgotten

artists.

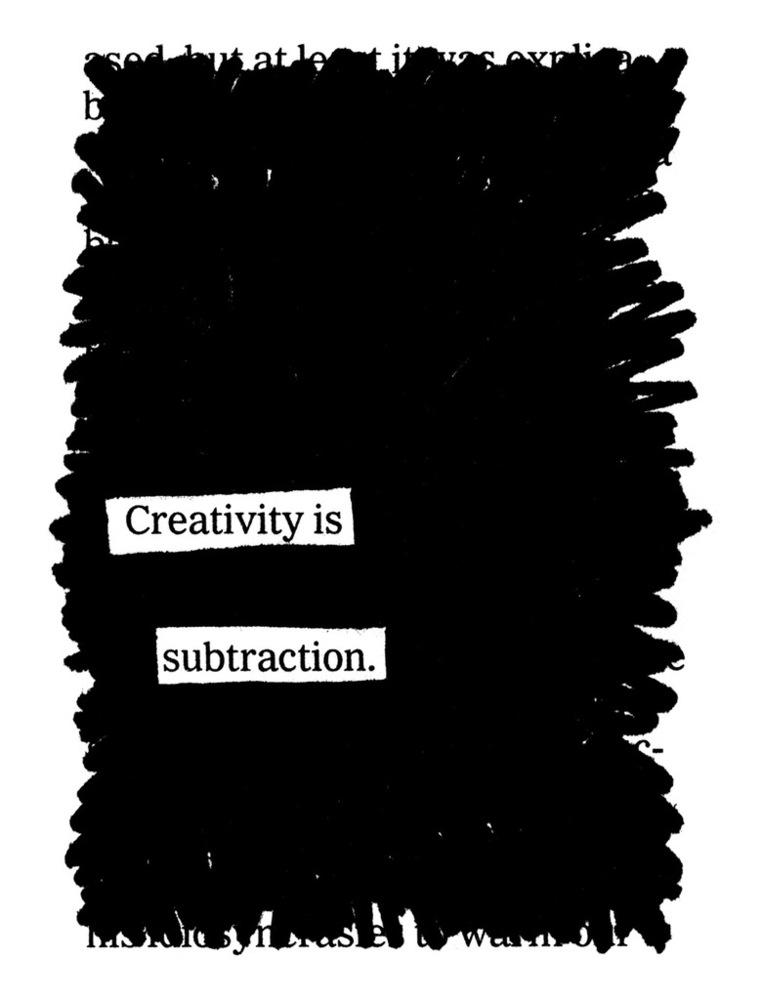

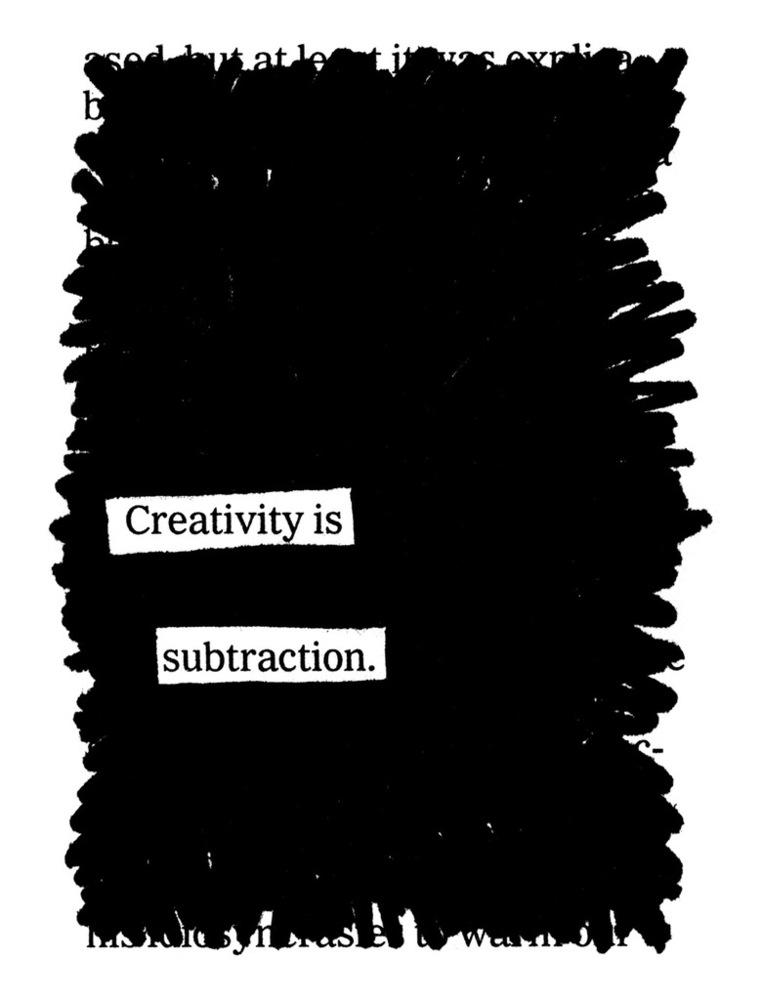

Meanwhile, artist

Austin

Kleon, author of the wonderful

Steal Like an Artist, celebrates the

negative space of the creative act in his

Newspaper

Blackout masterpiece:

But perhaps, after all, we should heed

Charles

Eames’s admonition:

Recent years have shown a growing preoccupation with the

circumstances surrounding the creative act and a search for the

ingredients that promote creativity. This preoccupation in itself

suggests that we are in a special kind of trouble — and indeed we are.

“Creativity” is one of those grab-bag

terms, like “happiness” and “love,” that can mean so many things it runs

the risk of meaning nothing at all. And yet some of history’s greatest

minds have attempted to capture, explain, describe, itemize, and dissect

the nature of creativity. After similar omnibi of cultural icons’ most

beautiful and articulate definitions

“Creativity” is one of those grab-bag

terms, like “happiness” and “love,” that can mean so many things it runs

the risk of meaning nothing at all. And yet some of history’s greatest

minds have attempted to capture, explain, describe, itemize, and dissect

the nature of creativity. After similar omnibi of cultural icons’ most

beautiful and articulate definitions